The Century Homes of Bath; The Jonathan Hale House and Farm

Editor’s note: The Century Homes Committee of the Bath Township Historical Society (BTHS) is recognizing the “Century Homes” in Bath. Each month, a century home is selected for a narrative and photographic exhibit at the Bath Museum. Historical society members are undertaking this project for Bath’s 2018 bicentennial. They hope to recognize all of the century homes in Bath. BTHS member Libby Bauman provided this month’s story.

As the Bath Township bicentennial celebration continues throughout 2018, we revisit the story where the settlement began in 1810. Most of this story was originally featured in the Bath Country Journal in October 2010.

More than 200 years have passed since Jonathan Hale first set foot in Township 3, Range 12 of the Connecticut Western Reserve. It was first called Wheatfield, later Hammondsburg, and is now known as Bath Township.

Born in 1777 in Glastonbury, Conn., Hale set out for a new life in the Connecticut Western Reserve in July 1810. He journeyed alone to prepare the land for his family. His sisters Rachel (Hale) Hammond and Sarah Hale and their families planned to head west a few months later with his wife Mercy (Piper) Hale and their children: Sophronia, 6, William, 4, and Pamelia, 2. Jason and Rachel Hammond sent their oldest son, Theodore, to choose their lots, but Hale and Theodore never met along their journeys.

Hale found that Abraham Miller had built a log cabin and cleared some land on his chosen property. He gave Miller a horse and wagon in exchange for his efforts. The cabin was home to the Hale family for the next 15 years.

The extended family arrived in Hammondsburg in November 1810. Hale and Mercy’s first child born in the settlement was Andrew on Dec. 5, 1811. They had two more children in Bath, Abigail and James.

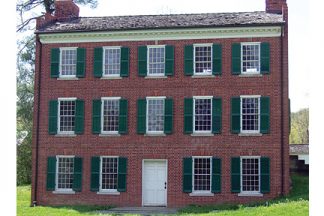

Bath Township was founded in 1818, and Hale began planning his permanent home in 1824. The land, in the valley near the Cuyahoga River, provided clay necessary to make bricks, and the plentiful lime was burned for mortar. Hale’s concept of a brick Federal Style home was quite new to pioneer families. The Hale house is one of the earliest brick structures in the Cuyahoga Valley.

The original home was built between 1825-1827. Hale sought the assistance of John Bosworth for its construction. Bosworth, a skilled builder, carpenter and craftsman, was the husband of Hale’s niece, Eveline.

The home consists of a large three-story section facing Oak Hill Road. Built into a slope, the first floor has no rear windows. This floor had the all-purpose “keeping room,” which contained the kitchen, dining and living areas. This was reminiscent of the single room of the old log cabin, but it also has similarities to today’s open-concept “great room.”

The second floor was more formal. It provided a parlor for special occasions with an exterior door for company. It also had what was likely a formal dining room, but this room was later used as a bedroom. In May 1827, Sophronia Hale married Ward K. Hammond in the parlor of the new homestead, the walls still not plastered.

The third floor was originally divided into six small bedrooms. There were no fireplaces (and no heat) on this floor. The layout was later changed to allow for larger bedrooms. The Hales lovingly called their new home “Old Brick.”

In 1828, shortly after the original house was completed, Hale’s oldest son William married Sally Upson. A 1 ½-story addition was built as a living room for the entire family, and William and Sally set up house on the first floor.

Mercy died in October 1829. Hale considered selling his interest in the farm and other lands so he could return to Connecticut. Instead, he decided to stay, and in November 1830, he married Sarah Cozad Mather. They had three children: Jonathan (1831), Mercy Ann (1835) and Samuel (1838).

In 1838, Andrew Hale married Jane Cozad Mather. He built a small home across the street for his family. It was later moved and attached to Old Brick’s living room, forming the south wing. A north wing addition was built as a storage house for coal and other supplies. These wings, originally clapboard siding, were faced in brick in the late 1950s.

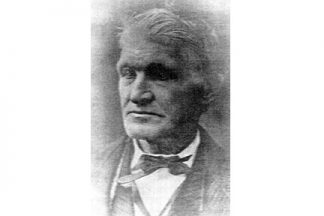

Andrew took over running the farm in 1844. He and Jane had six children: Pamelia (1838), Sophronia (1841), Clarissa (1843), Charles Oviatt (1850), Alida (1855) and John P. (1857). A large barn was built around 1850.

Hale died in 1854 and is buried in Ira Cemetery. His second wife Sarah died the following year.

Bath Township Historical Society’s collection contains a framed, matted photograph of Andrew. The mat reads “Andrew Hale … First White Child Born In Bath Township, Born Dec. 5th 1811 – Died July 30th 1884 Presented to Bath Township by J.P. Hale, May 31st 1909.”

In the photo, Andrew appears older, so it may have been taken circa 1870-1880. John P., Andrew’s youngest son, presented the photograph to the township to preserve his father’s legacy.

Andrew built another barn in 1866. The large family continued to live in Old Brick and run the farm.

In 1875, Charles Oviatt (C.O.) married Pauline Cranz. When the Hammond family moved further west, the Cranz family purchased their home (Bath Country Journal, August 2008). When Andrew died in 1884, C.O. inherited the home and surrounding 97 acres. He hired his nephew Carl Cranz as a tenant farmer.

C.O. and Pauline began to offer their home as a “summering house,” inviting guests from the city to stay in the country for a weekend, a week or the entire summer. It became known as Hale Inn. C.O. was the host and was called “the Squire,” while Pauline cooked and served meals to guests.

As explained in “The Jonathan Hale Farm, a Chronicle of the Cuyahoga Valley,” a book by John Joseph Horton, “It was a house with an informal charm all its own, and if there were occasional inconveniences, they were part of the fun. It was a relaxing place in a lovely setting of gardens, hedges, fruit trees, open meadow and farm land, framed by the forested hills. It seems clear that the engaging personalities of the Squire and his wife had the most to do with its popularity.”

Pauline died in 1924, and C.O. died in 1938. They never had children, so the future of the farm was uncertain. Their niece and nephew, Clara Bell and Ned Ritchie, bought the old homestead after C.O.’s death.

Clara never married and left the homestead to the Western Reserve Historical Society after her death in 1953, “to establish the Hale Farm and the buildings thereon as a museum.” The Western Reserve Historical Society acquired the farm in 1957.

The original brick exterior of the home has been replaced. The original clay was too soft to stand the test of time. Original brick survives in the cellar behind the basement room and in part of the rear wall of the home. Three original mantels continue to grace the homestead, as do the wide plank poplar floors of the parlor and third-floor bedrooms.

In April 1973, the Jonathan Hale homestead was the first property in Bath to receive National Register of Historic Places designation. This preservation effort by WRHS inspired research into other properties in the township that were worthy of National Register designation.

Hale Farm & Village is now an outdoor living history museum, providing visitors with a view of 19th century life on the Western Reserve. The Jonathan Hale homestead is the nucleus of the property, which contains 34 historic structures. This year, WRHS is celebrating 60 years of operating the museum.

Hale Farm is open weekends in October from 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Admission is $10 for adults and $5 for children 3-12. Visit wrhs.org and click on “Hale Farm & Village” for information about upcoming programs.

Featured image photo caption: A photo shows the Hale House circa 1890.